What to keep, what to delete?

Contents

- A cruel absence of consensus

- Why not keep everything?

- How to choose?

- Reasons for preserving data

- Legal or contractual obligations

- Scientific value of data

- Technical criteria

- How long should data be kept?

- When should all these decisions be made?

- Perspectives and conclusion

A cruel absence of consensus

Despite data publication becoming a requirement, there is still no consensus about which data should be kept long-term.

Why not keep everything?

Due to technological developments and different measurement instruments used in research, the volume of digital research data requiring processing and preservation is increasing exponentially.

To those who say “keep everything!”, Whyte and Wilson (1) make 4 objections:

- Quantities of research data are increasing excessively. Certain disciplines, such as astronomy and particle physics, are now generating several TB every day.

- Copies made for securing data at least double the cost of data preservation.

- It is becoming increasingly difficult to find data of interest.

- The management and retention costs time and money, outlays that you can dispense with for data that does not need to be kept.

It is also important to ask yourself if the data can be used by others. Are the descriptions correct? Are they saved in a format that will allow them to be reused?

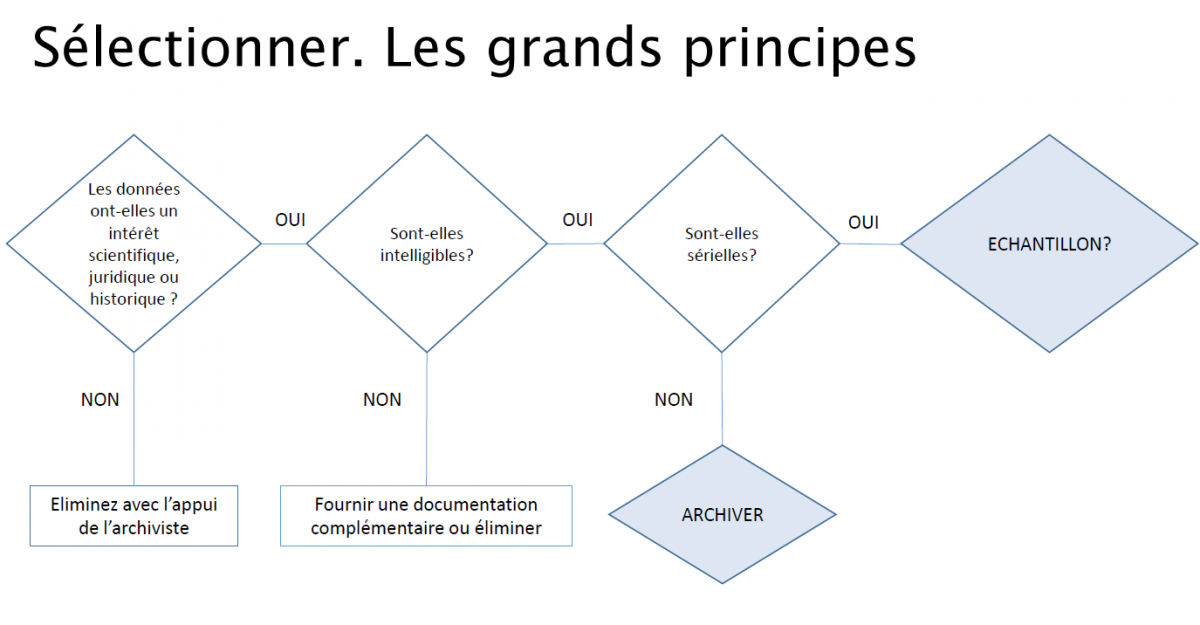

The flow-chart below presents the main principles of data selection for archiving.

How to choose?

It has become necessary to assess and choose which data should be preserved. In its report entitled “What to keep?” the JISC (Joint Information Systems Committee) (2) summarized the key issues:

- What should be kept?

- Why?

- For how long?

- Where?

- How?

Unfortunately, there is no single answer to any of these questions. Differences between research disciplines, and even between different sub-disciplines of the same research field, are too great. For some communities, using old data is an integral part of the working method. This is the case for marine ecosystem specialists who rely on data from the International Council for Exploration of the Sea, which includes data sets from over 100 years ago (3).

Despite the disparity between disciplines, there are several general recommendations.

Reasons for preserving data

Tjalsma and Rombouts (4) identify 3 main reasons for preserving research data over the long-term:

- Reusing data by the same research team or not, in the same research discipline or not, etc.

- Checking data and discoveries made based on them (peer evaluation, public confidence in academic or private research, etc.

- Retention for reasons of heritage (historical research, history of science, national and international cultural heritage, etc.)

Legal or contractual obligations

In each case, the question of obligations for long-term data preservation must be addressed – either legal, imposed by research funders or by scientific journal publishers, etc. (for more information, see the articles about funding agency requirements and scientific journal publishers).

It is also important to take into account any obligations to dispose data (e.g. private data or collected for a specific use for which people have given their consent).

Scientific value of data

Once legal, regulatory and contractual considerations have been addressed, other criteria can be taken into account:

- What is the current value of the data, and potential value for the future? (current value and estimated future value)

- Scientific / historical / cultural value

- Financial value: production costs; potential preservation costs

- Is the data unique ? What is the risk related to its loss? Can it be replicated? (e.g. astronomical observation of a unique event)

Researchers, creators, and users of data are often the best placed to evaluate the value and uniqueness of their data. As part of the project NanOQTech, coordinated by the CNRS and involving inorganic chemistry, atomic and quantum optics physics groups amongst others, researchers estimate that the long-term preservation of data is “important” because of the “highly prospective” nature of NanOQTech, which may detect “future developments completely unknown at this time”.

Technical criteria

ITechnical criteria for the storage of data also feature in reports and documents featuring guidelines about the subject (4, 5 and 6).

Technical criteria alone do not suffice for decisions to be made about long-term preservation. It is, however, necessary to clarify them before making a decision.

- Which formats are used and why (open/proprietary, which software, in which versions, etc.)?

- Is the description of the data, in the form of metadata, accessible and sufficient for reuse?

- What types of data (raw, processed, published, etc.)?

- What restrictions of access and of use of data (licences, copyright, patents, etc.)?

- How is the data preserved? Which facilities institutional databases, discipline-based or multidisciplinary warehouses, which one or ones, etc.?

- What are the costs of data preservation and how will they be covered? Who will pay?

For how long must data be kept?

Some research and higher educational institutions have already begun to define guidelines to help their researchers make these decisions. But once again, there is no single answer for researchers in institutions which do not yet have data preservation policies.

Preservation periods recommended to researchers vary a lot in the examples of data preservation policies:

5 years after the end of the project in the Netherlands code of conduct for scientific practices; and 10 years in the University of Cambridge’s data preservation guide.

Institut Pasteur indicates that as laboratory notebooks are preserved for 25 years, the same must apply to research data. (7, 8 et 9)

Preservation periods for research data are not specified for projects financed by the Horizon 2020 program. However, article 18 of the funding agreement specifies that documents justifying budgets, for example, must be kept for at least 5 years after payment of the final sum. This period can be decreased to 3 years for shorter projects. (10)

As a result, some projects choose to preserve their research data for the same 5-year period. This is the case for the POLYPHEM project working on small-scale solar power plants. (11)

Recurring interest in data related to clinical trials and astronomical or environmental observations suggests they should be preserved even longer.

When should these decisions be made?

Archivists, librarians and data-management experts are categoric: the earlier decisions are made about data retention during their creation process, the better the conditions for preservation can be anticipated (legal and contractual obligations, technical format criteria, descriptions, data set structures, costs and funding, etc.).

Yet it is difficult to foresee the future value of a data set, even more so if its precise content is unknown. Decisions must therefore be able to evolve with a project.

For example, the value of ESA (European Space Agency) data has been re-evaluated since the creation of the growing problem of climate change.

Perspectives and conclusion

The management and preservation of research data is a constantly evolving field. Currently sketchy criteria for data selection and validation are sure to vary rapidly in the coming years.

Making progress in this discipline is important. For those that have not yet done so, research disciplines and sub-disciplines – even research units initially – must develop evaluation and selection criteria adapted to the data they create and use.

To enable discipline-based and multidisciplinary communities of researchers to develop these criteria, all the stakeholders must exchange in order to:

- harmonize requests and conditions of funding bodies, research organizations and institutions;

- define common rules for the assessment of research and researchers for the importance of data;

- establish funding conditions for research data preservation.

- Whyte, A. & Wilson, A. (2010). “How to Appraise and Select Research Data for Curation”. DCC How-to Guides. Edinburgh: Digital Curation Centre. Accessible on-line : http://www.dcc.ac.uk/resources/how-guides

- Beagrie , Neil (2019) “What to Keep: A Jisc research data study”. [Publication] Accessible on-line : https://repository.jisc.ac.uk/7262/

- Task 7.2 of AtlantOS project: Data Management Handbook. Accessible on-line :https://www.atlantos-h2020.eu/download/7.4-Data-Management-Handbook.pdf

- Selection of Research Data, Guidelines for appraising and selecting research data, Heiko Tjalsma – Data Archiving and Networked Services (DANS), Jeroen Rombouts – 3TU.Datacentrum

- The NERC Data Value Checklist (NERC 2015 – first version issued in 2013)

- DCC (2014). ‘Five steps to decide what data to keep: a checklist for appraising research data v.1’. Edinburgh: Digital Curation Centre. Accessible on-line : http://www.dcc.ac.uk/resources/how-guides

- University of Cambridge: Statement of Records Management Practice and Master Records Retention Schedule. Accessible on-line: https://www.information-compliance.admin.cam.ac.uk/records-management

- Netherlands Code of Conduct for Scientific Practices

- Archiving / Long-term research data retention, Ceris and Institut Pasteur

- Version 5.2 of the funding convention model of the Horizon 2020 programme (26/06/2019) (H2020 AGA – Annotated Model Grant Agreement V5.2). Accessible on-line : https://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/data/ref/h2020/grants_manual/amga/h2020-amga_en.pdf

- D9.1 POLYPHEM Data Management Plan (Plan de gestion de données du projet POLYPHEM)

Accessible on-line : https://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/documents/downloadPublic?documentIds=080166e5be029c44&appId=PPGMS - NSB-05-40, Long-Lived Digital Data Collections Enabling Research and Education in the 21st Century. Accessible on-line : https://www.nsf.gov/pubs/2005/nsb0540/